By Steve Weisman

Fish move. But how much, and why? That has been the ongoing question of anglers and biologists for years. Understanding fish movement can have large implications for management of species, highlighting the importance of seasonal habitat usage and sources of mortality. In particular, muskies are roamers.

We know that when the water is high enough, many may leave the Iowa Great Lakes and go over the Lower Gar overflow. In October of 2019, modifications to the existing electric fish barrier were made in attempt to deter fish from migrating out of the Okoboji chain. It does not have the strength of the barrier that stops fish from coming upstream (bighead, silver carp) into the Iowa Great Lakes chain. Since that time, water levels have not been high enough to see how effective this system is.

However, studies have continued to help DNR Fisheries Biologists understand the movements of these fish. If there is an expert on muskie habits, it has to be DNR Fisheries Biologist, Jonathan Meerbeek. One of the most comprehensive studies currently underway began this past April checking on the movements of adult muskies. This study follows the travels of 26 tagged muskies from their tagging beginning on April 30 and lasting through September 20.

How it works

We’ve all seen the DNR boat with the big antenna following muskies. This is a very time-consuming process that can aid in determining fish habitat usage and survival during typically only a snapshot of the day. But what about the rest of the day, weeks and months? A new type of technology allows for continuous tracking of fish movements without lifting a finger through the use of technology.

For this study, the DNR strategically placed 19 acoustic receivers throughout the Okoboji chain (most were in East and West Okoboji) that “listen” for fish that have been fitted with acoustic tags that are constantly emitting a unique code that can only be heard by the acoustic receivers. Once a fish is “heard” by the receiver, it records the exact date and time the fish swam by. Biologists can then download this data periodically and determine the long-term movement of fish.

Over the course of five months, 697,405 individual fish detections were recorded! Since, tags will last 4-5 years, this will give true long-term data that will assist in managing this unique fishery. Generally speaking, what researchers found was that muskellunge move a ton, both among the lake chain and even within an individual lake. For example, of the 26 tagged broodstock muskies, 17 moved from at least one lake to another over the summer, and one fish made 11 different trips between East and West Okoboji from May to early June!

A wanderer’s story

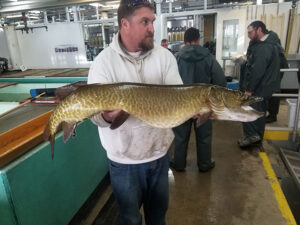

Perhaps the greatest muskie wanderer was tag #57715, a 47” female at an age of 21. She had been stocked as a yearling in 2002. Data collected over the years, shows she had been captured by DNR nets seven times between 2010-2022 and spawned during at least four of those years. All her captures came from East Okoboji Lake.

This is the story of her journey beginning on April 30…

After being spawned, she was stocked back into East Okoboji Lake at the HWY 9 boat ramp. She stayed there until May 2 and then moved to the Stony Point area until May 6. Between May 6 and May 23, she made five different trips from Stony Point all the way to the lower end of East Okoboji. Meerbeek said, “It was like she was doing hot laps!” From May 24 through May 26, she went from the HWY 9 Bridge area to the Triggs Bay area near the Trestle.

Then on May 27, she entered West Okoboji’s Smiths Bay. In less than 12 hours, she went all the way to the north end of West to the Triboji area. She stayed there until early June. From June 3-8, she made three trips from the North Bay to Atwell’s Point and back.

From June 9-15, she was at Atwell’s Point and traveled to Fort Dodge. Then from June 15-18, she was back at the North Bay. Suddenly, she headed south to Millers Bay. From June 19th to September 20th, the fish roamed around the southern half of West Okoboji Lake, never residing anywhere longer than a few days. This was perhaps the most interesting observation, as large female muskellunge are traditionally thought to be more reclusive and limited in their movements during summer. She, to say the least, was neither!

Then came September 14, when she made a trip to East Okoboji for 21 hours and then headed back to Smiths Bay.

ALL TOTAL: 36,282 detections and she was detected on all but five days of the study! What detailed data! Over the course of the next four to five years, think of the data that can be collected and what the biologists will learn about musky habits.

Getting ready to place one of the acoustic receivers in the lake.

The 21-year old 47” muskie captured last spring during the spawning season is now known as “the wanderer” for her documented journey this past summer on the Okoboji chain.